Share This

Album at a Glance

Tags

Related Posts

- Gaetano Veneziano (1665-1716): In Officio Defunctorum - Nocturns for the Dead / Ensemble Odyssee

- Music for Brass Septet, Vol. 2 - Instrumental suites from operas by Rameau, Blow, Purcell & Handel / Septura

- Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975): Orchestral Works

- Carson Cooman: ‘In Beauty Walking’ - Orchestral Works / Leah Crane, soprano; Chloé Trevor, violin

Orfeo(s): Italian & French Cantatas / Sunhae Im, soprano; Berlin Early Music Academy

Posted by George Adams on Aug 26, 2015 in Baroque | 0 comments

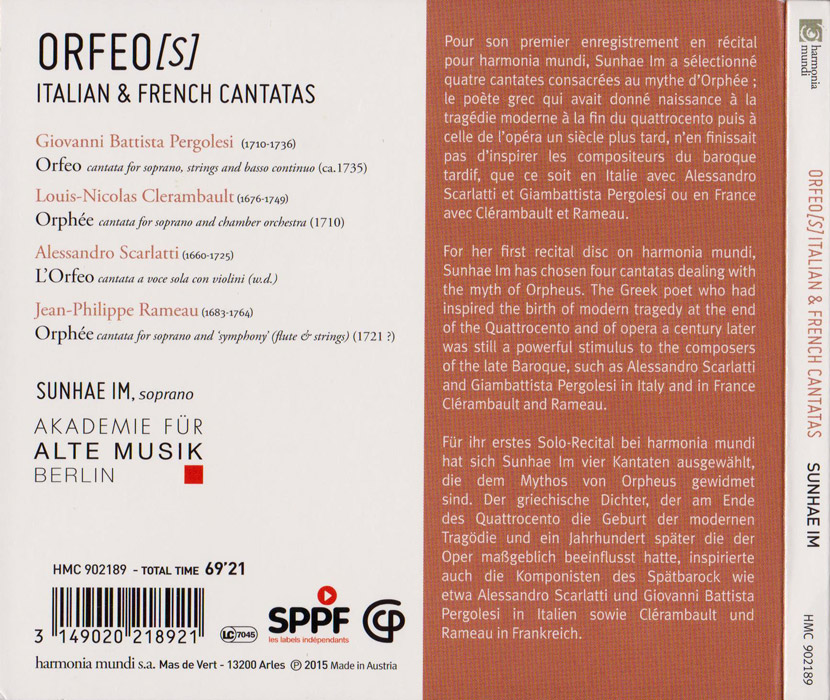

Harmonia Mundi’s collection of cantatas on the story of Orfeo is exactly what I want from new recordings of early music. The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin and Sunhae Im are exemplary in their playing and singing; the audio engineering and sound quality are deeply satisfying; and the perspectives of several composers on one character provide historical insight not available elsewhere. Perhaps the most famous Orfeo is Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo from 1607, but each of these pieces was written about 100 years later. The prevailing music styles changed significantly over this time, moving toward a much more familiar classical tonality and set of musical-dramatic conventions.

First is Giovanni Battista Pergolesi’s Orfeo (c.1735), for soprano, strings, and basso continuo. This cantata consists of two pairs of recitative and aria, briefly recounting the story of Eurydice’s fate in hell and Orfeo’s determination to rescue her, no matter the cost. Some passages sound positively Mozartian, but occasional chromaticism sets Pergolesi’s music apart from the merely generic. Written approximately one year before his death at the age of twenty-six, this short cantata is yet another tantalizing hint at what could have been.

Louis Nicolas Clérambault’s Orphée (1710) is a cantata for soprano and chamber orchestra, a more expansive instrumentation than Pergolesi’s contribution. Although it is roughly as long as the previous cantata, Clérambault’s is divided into four pairs of recitative and aria. It does not cover any more of the plot, but it certainly feels more restless and anxious, less willing to dwell on any one moment. Constant trading back-and-forth between singer and ensemble lends mobility and vitality to the music, sometimes at the expense of a sense of depth and reflection. This cantata is from the French composer’s earliest published collection, but represents the height of his dramatic writing.

Alessandro Scarlatti is known for his remarkably prolific output, numbering around 100 operas and 800 cantatas. (He is not to be confused with his son Domenico, who is famous for his 555 keyboard sonatas.) Amidst this ocean of music is his cantata L’Orfeo, which is likely the earliest of the pieces featured here, though its exact date is uncertain. It shows a remarkable penchant for harmonic exploration and a personal style recognized by his contemporaries. During his career, Scarlatti enjoyed very comfortable, high-paid positions that allowed him indulgences, musical and otherwise. With this flexibility came music that looked both backward and forward, combining the sounds of older music with an expressive mindset that was relatively new. The light, floating aria at the heart of the cantata, Sordo il tronco, is a perfect example of the musical freedom this comfort afforded. In a tranquil F major, Orfeo reflects on the power his song has over nature and even the creatures of Hell.

The final cantata is by Jean-Philippe Rameau, composer and music theorist. His cantata, unsurprisingly titled Orphée, is for soprano and “symphony”—in this case strings, continuo, and flute. Of the works here, his is the only to narrate the ending of the story, Orfeo’s glance back at Eurydice that costs her eternity in the underworld. The other cantatas refer to this tragic conclusion, but Rameau describes it in detail in recitative. The final aria, though, is a cheerful recitation of the lesson we all ought to learn from Orfeo’s mistake. It resembles the closing choruses of many Enlightenement-era operas that served as opportunities for a moral or ethical takeaway from the tale. Here Rameau, through the story of Orfeo, warns us to be patient: “Many a man would be happy today had he not desired his happiness too soon.”

For her first recital disc on harmonia mundi, Sunhae Im has chosen four cantatas dealing with the myth of Orpheus. The Greek poet who had inspired the birth of modern tragedy at the end of the Quattrocento and of opera a century later was still a powerful stimulus to the composers of the late Baroque, such as Alessandro Scarlatti and Giambattista Pergolesi in Italy and in France Clérambault and Rameau.

Source: harmonia mundi

Alessandro Scarlatti |

Alessandro Scarlatti, composer Alessandro Scarlatti (2 May 1660 – 22 October 1725) was an Italian Baroque composer, especially famous for his operas and chamber cantatas. He is considered the founder of the Neapolitan school of opera. He was the father of two other composers, Domenico Scarlatti and Pietro Filippo Scarlatti. Scarlatti’s music forms an important link between the early Baroque Italian vocal styles of the 17th century, with their centers in Florence, Venice and Rome, and the classical school of the 18th century. Scarlatti’s style, however, is more than a transitional element in Western music; like most of his Naples colleagues he shows an almost modern understanding of the psychology of modulation and also frequently makes use of the ever-changing phrase lengths so typical of the Napoli school. Source: Wikipedia

|

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault |

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault, composer Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (19 December 1676 – 26 October 1749) was a French musician, best known as an organist and composer. He was born, and died, in Paris. Clérambault came from a musical family (his father and two of his sons were also musicians). While very young, he learned to play the violin and harpsichord and he studied the organ with André Raison. Clérambault also studied composition and voice with Jean-Baptiste Moreau. Clérambault became the organist at the church of the Grands-Augustins and entered the service of Madame de Maintenon. After the death of Louis XIV and Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers, he succeeded the latter at the organ of the church of Saint-Sulpice and the royal house of Saint-Cyr, an institution for young girls from the poor nobility. He was responsible there for music, the organ, directing chants and choir, etc. It was in this post—it remained his after the death of Madame de Maintenon—that he developed the genre of the “French cantata” of which he was the uncontested master. In 1719 he succeeded his teacher André Raison at the organs of the church of the Grands-Jacobins. His Motet du Saint Sacrement in G major is one of the first French works known to have been performed in Philadelphia. Source: Wikipedia

|

_-_001.jpg) Jean-Philippe Rameau |

Jean-Philippe Rameau, composer Jean-Philippe Rameau (25 September 1683 – 12 September 1764) was one of the most important French composers and music theorists of the Baroque era. He replaced Jean-Baptiste Lully as the dominant composer of French opera and is also considered the leading French composer for the harpsichord of his time, alongside François Couperin. Little is known about Rameau’s early years, and it was not until the 1720s that he won fame as a major theorist of music with his Treatise on Harmony (1722) and also in the following years as a composer of masterpieces for the harpsichord, which circulated throughout Europe. He was almost 50 before he embarked on the operatic career on which his reputation chiefly rests today. His debut, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), caused a great stir and was fiercely attacked by the supporters of Lully’s style of music for its revolutionary use of harmony. Nevertheless, Rameau’s pre-eminence in the field of French opera was soon acknowledged, and he was later attacked as an “establishment” composer by those who favoured Italian opera during the controversy known as the Querelle des Bouffons in the 1750s. Rameau’s music had gone out of fashion by the end of the 18th century, and it was not until the 20th that serious efforts were made to revive it. Today, he enjoys renewed appreciation with performances and recordings of his music ever more frequent. Source: Wikipedia |

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi |

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, composer Giovanni Battista Draghi (4 January 1710 – 16 March 1736), best known as Pergolesi or Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, was an Italian composer, violinist and organist. Born in Jesi in what is now the Province of Ancona (but was then the Papal States), he was commonly known by the nickname “Pergolesi,” a demonym indicating in Italian the residents of Pergola, Marche, the birthplace of his ancestors. He studied music in Iesi under a local musician, Francesco Santini, before going to Naples in 1725, where he studied under Gaetano Greco and Francesco Feo among others. He spent most of his brief life working for aristocratic patrons like the Colonna principe di Stigliano, and duca Marzio IV Maddaloni Carafa. Pergolesi was one of the most important early composers of opera buffa (comic opera). His opera seria, Il prigionier superbo, contained the two act buffa intermezzo, La serva padrona (The Servant Mistress, 28 August 1733), which became a very popular work in its own right. When it was performed in Paris in 1752, it prompted the so-called Querelle des Bouffons (“quarrel of the comic actors”) between supporters of serious French opera by the likes of Jean-Baptiste Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau and supporters of new Italian comic opera. Pergolesi was held up as a model of the Italian style during this quarrel, which divided Paris’s musical community for two years. Among Pergolesi’s other operatic works are his first opera La conversione e morte di San Guglielmo (1731), Lo frate ‘nnamorato (The brother in love, 1732, to a text in the Neapolitan language), L’Olimpiade (31 January 1735) and Il Flaminio (1735). All his operas were premiered in Naples, apart from L’Olimpiade, which was first given in Rome. Pergolesi also wrote sacred music, including a Mass in F and his Magnificat in C major. It is his Stabat Mater (1736), however, for soprano, alto, string orchestra and basso continuo, which is his best-known sacred work. It was commissioned by the Confraternità dei Cavalieri di San Luigi di Palazzo who presented an annual Good Friday meditation in honor of the Virgin Mary. Pergolesi’s work replaced one composed by Alessandro Scarlatti only nine years before, but which was already perceived as “old-fashioned,” so rapidly had public tastes changed. Source: Wikipedia |

|

Sunhae Im |

Sunhae Im, soprano The Korean soprano, Sunhae Im (Born January 15, 1976 in Cholwon, South Korea) studied from 1994 to 1998 at the College of Music/Seoul National University and with Roland Hermann at the Hochschule für Musik in Karlsruhe. In 1997 she won First Prize at the Korean Schubert Society Competition and the Grand Prix of the tenth Korean Youth and Music Competition. In May 2000 she was finalist in the Reine Elisabeth Song Competition in Brussels. In February 2000 Sunhae Im was heard as Barbarina in W.A. Mozart’s Nozze di Figaro under Paolo Carigniani at the Frankfurt Opera. In the following season she sang Valetto and Amor in Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea(Frankfurt). From 2001 - 2004 she was a member of the Hannover Opera and was heard in roles such as Zerlina, Blondchen/Entführung aus dem Serial, Barbarina/Nozze, Papagena/Zauberflöte, Adele/Fledermaus, Cupido/Orpheus by Offenbach and Yniold in Pelleas et Mélisande. Source: Bach Cantatas Bio |

|

Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin |

Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, ensemble Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin (Academy for Ancient Music Berlin, short name: Akamus) is a German chamber orchestra founded in East Berlin in 1982. Each year Akamus gives circa 100 concerts, ranging from small chamber works to large-scale symphonic pieces in Europe’s musical centers as well as on tours in Asia, North America and South America. About 30 musicians form the core of the orchestra. They perform under the leadership of their four concertmasters Midori Seiler, Stephan Mai, Bernhard Forck and Georg Kallweit or guest conductors like René Jacobs, Marcus Creed, Daniel Reuss, Peter Dijkstra and Hans-Christoph Rademann. Recording exclusively for harmonia mundi France since 1994, the ensemble’s CDs have earned many international prizes, including the Grammy Award, the Diapason d’Or, the Cannes Classical Award, the Gramophone Award and the Edison Award. In 2011 the recording of Mozarts Magic Flute was honoured with the German Record Critics’ Award. In 2006 the Recorder Concertos by G. Ph. Telemann with Maurice Steger have received a number of the most important international awards. Ever since the reopening of the Berlin Konzerthaus in 1984, the ensemble has its own concert series in Germany’s capital. Furthermore it has regularly been guest at the BerlinStaatsoper Unter den Linden, Philharmonie Berlin, De Nederlandse Opera in Amsterdam, at the Innsbruck Festival of Early Music and the Carnegie Hall New York. The ensemble works regularly with the RIAS Kammerchor as well as with soloists like Cecilia Bartoli, Andreas Scholl, Sandrine Piau and Bejun Mehta. Moreover, Akamus has extended its artistic boundaries to work together with the modern dance company Sasha Waltz & Guests for productions of Dido and Aeneas (music: Henry Purcell) and Medea (music: Pascal Dusapin). Source: Wikipedia |

![]() About George Adams

About George Adams

Twitter •

| Thinking about purchasing this album?

Follow this link for more album details or to make the purchase. Buy it now |

“Not just recommended. Guaranteed.”

We stand behind every album featured on Expedition Audio. Our objective is to take the monetary risk out of music exploration. If you order this album from HBDirect.com and do not like it you can return it for a refund.

Handel: Agrippina - Poppea / Sunhae Im